The Pilot-Owner, Not the Aircraft Mechanic, Should Take Charge of Troubleshooting

I’ve observed a surprising behaviour among many aircraft operators over the years. Strangely enough, when pilots leave their aircraft at a maintenance shop, they often grant carte blanche for all tasks, necessary or not, to ensure airworthiness. Without questioning the need or reason, they seem to hand over the reins of responsibility to their mechanic whenever maintenance looms or issues arise. How do I know this? I’ve done the same, both as a pilot and head of flight operations, before gaining a deeper insight into aircraft operations and maintenance.

We’ve touched on the importance of taking control of your aircraft maintenance in previous discussions, but it bears repeating. Advanced pilots don’t shy away from their responsibility regarding aircraft airworthiness, especially when issues crop up. Pilot-owners must own their aircraft’s maintenance and tackle troubleshooting systematically and professionally.

Identify, Test & Verify, Then Fix!

For effective and efficient troubleshooting, a structured approach is essential. Troubleshooting unfolds in two distinct phases, much like airworthiness reviews or annual inspections: Diagnosis (Inspection) and Repair. The diagnosis involves several steps to ensure accurate cause identification before any rectification and should proceed as follows:

- Check for obvious reasons.

- Gather pertinent information and compile a symptoms list.

- List potential causes of the symptoms.

- Prioritise the list of potential causes.

- Conduct tests to confirm the diagnosis.

Check for Obvious Reasons

Before diving into troubleshooting, first examine any evident causes potentially triggering the issue in question. Sometimes, simply mishandling aircraft systems can simulate a problem that doesn’t truly exist. Examples might include selecting the incorrect fuel pump or tank in multi-engine aircraft, activating the wrong magnetos/ignition system, choosing an incorrect navigation source, mismanaging the audio panel, and more. Ensure all systems function correctly before delving into in-depth troubleshooting.

Gather Pertinent Information and Compile a Symptoms List

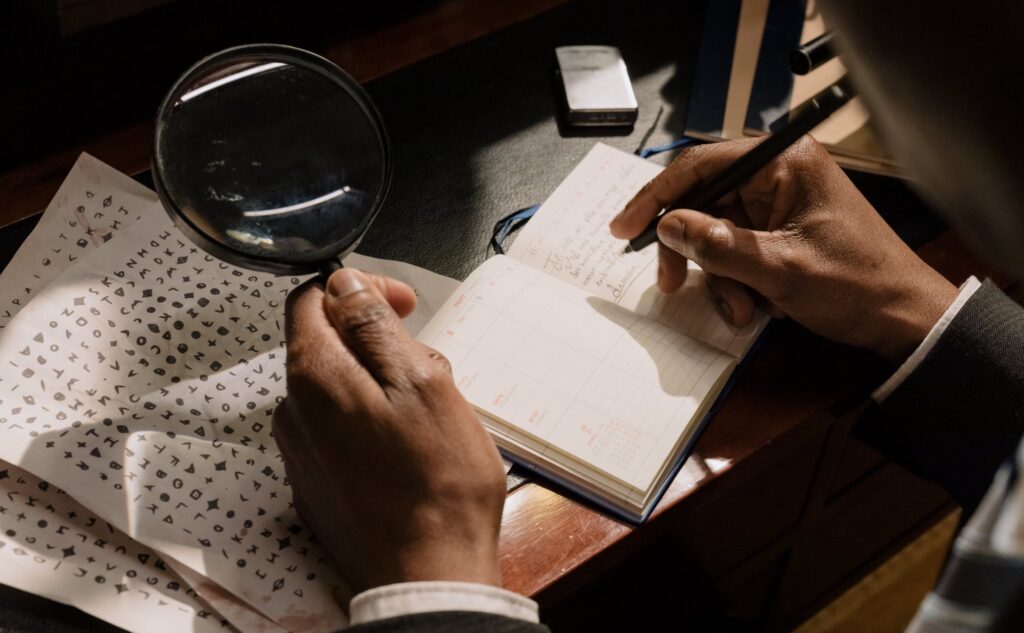

When an issue arises, methodically collect all relevant data related to the suspected problem and create a list of symptoms. Especially when facing intermittent issues, it’s crucial to approach this in an organised manner. Document your findings systematically, noting if observations change under different conditions like power settings (MAP, RPM, Mixture), radio frequencies, flaps/landing gear configurations, and so on. With enough data in hand, you can begin pinpointing potential causes.

List Potential Causes of the Symptoms

A thorough understanding is crucial to formulate theories about potential causes. This knowledge can often be sourced from books, manuals, data sheets, and bulletins. Another invaluable information source includes your mechanic, type-specific associations, and online forums. However, always critically evaluate this information for its reliability and trustworthiness.

Prioritise the List of Potential Causes

Prioritise potential causes considering their likelihood, testing feasibility, and associated costs. Some issues are more likely than others, and this likelihood can stem from logical reasoning, technical data, or past experience. The means to test these potential causes vary widely. Some tests might need basic tools like a multimeter or compression tester, while others necessitate specialised equipment. Occasionally, you might need to test theories by replacing parts, which should be a last resort. However, sometimes parts can be temporarily swapped (e.g. temperature probes) to economise on troubleshooting if a theory proves incorrect.

Organise potential causes by their likelihood (from most to least likely), ease of testing (from simplest to most complex), and replacement costs (from least to most expensive).

Conduct Tests to Confirm the Diagnosis

Once you’ve organised your list of potential causes, devise a plan to test these theories. Execute these tests to pinpoint the actual problem, preferably using a process of elimination. Rule out any item that has either been tested or can be discounted for other reasons. Often, certain theories can be dismissed based on specific symptoms. Ensure you address the root cause, rather than merely alleviating symptoms.

Rectify and Repair

Once you’ve successfully pinpointed the issue, it’s time to address it. Either tackle the issue yourself – if legally permissible – or employ an aircraft mechanic. Always secure a written agreement before green-lighting any work.

To be Avoided: Alternative Approaches

While a structured method is ideal for troubleshooting, it’s not always the norm. Alternative tactics include trial and error, “Educated Best Guess,” and the overkill method. Both pilot-owners and mechanics sometimes use these costly approaches. Hence, pilot-owners must shoulder their responsibility to accurately determine and confirm issues, ensuring they don’t spend excessively.

Trial and Error

This prevalent alternative often becomes a costly endeavour. Instead of a methodical search for the root cause, various (often expensive) parts are replaced in hopes of finding the solution. Parts chosen often depend on their availability and price. Sometimes, inexplicably, the priciest parts get replaced first. On the rare occasion, the problem might be fixed early, but often, this approach burns a hole in your pocket.

Educated Best Guess

Many resort to this guessing game. Rather than methodically identifying potential culprits, a “best guess” is made. If you’re fortunate, this guess might hit the mark. If not, you’re left with a hefty bill.

Overkill

This approach is the most detrimental. It entails doing – and paying – far more than necessary. For instance, opting for a top overhaul for a minor cylinder issue, or a complete engine overhaul due to a few metal flakes in the oil filter. Typically, these responses are excessive for the actual problem at hand.

Intermittent Problems

Sporadic issues that don’t manifest on the ground are the toughest to diagnose. When mechanics are left to handle these alone, they often resort to costlier alternative methods. If you’re unable to pinpoint the issue, consider taking your mechanic on a flight. For non-flight safety concerns, you might wait for the intermittent issue to either self-resolve or escalate, making diagnosis simpler.

Conclusion

Navigating the complex world of aircraft maintenance and troubleshooting can be daunting. However, as emphasised throughout this post, the pilot-owner plays a pivotal role in ensuring the aircraft’s optimal functionality. By actively engaging in the troubleshooting process, pilot-owners can exercise better control, reduce unnecessary costs, and ultimately foster a deeper connection with their aircraft. Shifting from reactive to proactive approaches, like structured troubleshooting, can make a world of difference. Remember, taking responsibility for troubleshooting doesn’t just save money – it cultivates an enriched understanding of your aircraft and reinforces a commitment to airworthiness and safety.

About Quest Aeronautics

Quest Aeronautics is a state-certified engineering office for aviation, dedicated to shaping the future of general aviation by providing innovative and cost-effective solutions to enhance aircraft performance and operations. With a focus on CS/FAR-23 and experimental/amateur-built (E/A-B) aircraft, Quest Aeronautics provides a range of services including flight testing, aircraft operations and maintenance consulting, high-quality aviation products, and tailored support for E/A-B projects. Collaborating with industry-leading partners, Quest Aeronautics is committed to delivering unparalleled support and expertise to individuals and organisations in the general aviation market.

About Author

Sebastian, the founder of Quest Aeronautics, is a driven and enthusiastic individual with a passion for aviation. Before delving into aviation, he gained valuable experience as a chemical process engineer and laboratory technician. Sebastian holds a Master of Science in Engineering and a commercial pilot licence, with several fixed-wing aircraft ratings under his belt. He has also completed an introduction course for fixed-wing performance and flying qualities flight testing at the National Test Pilot School in Mojave, CA and is compliance verification engineer for flight.